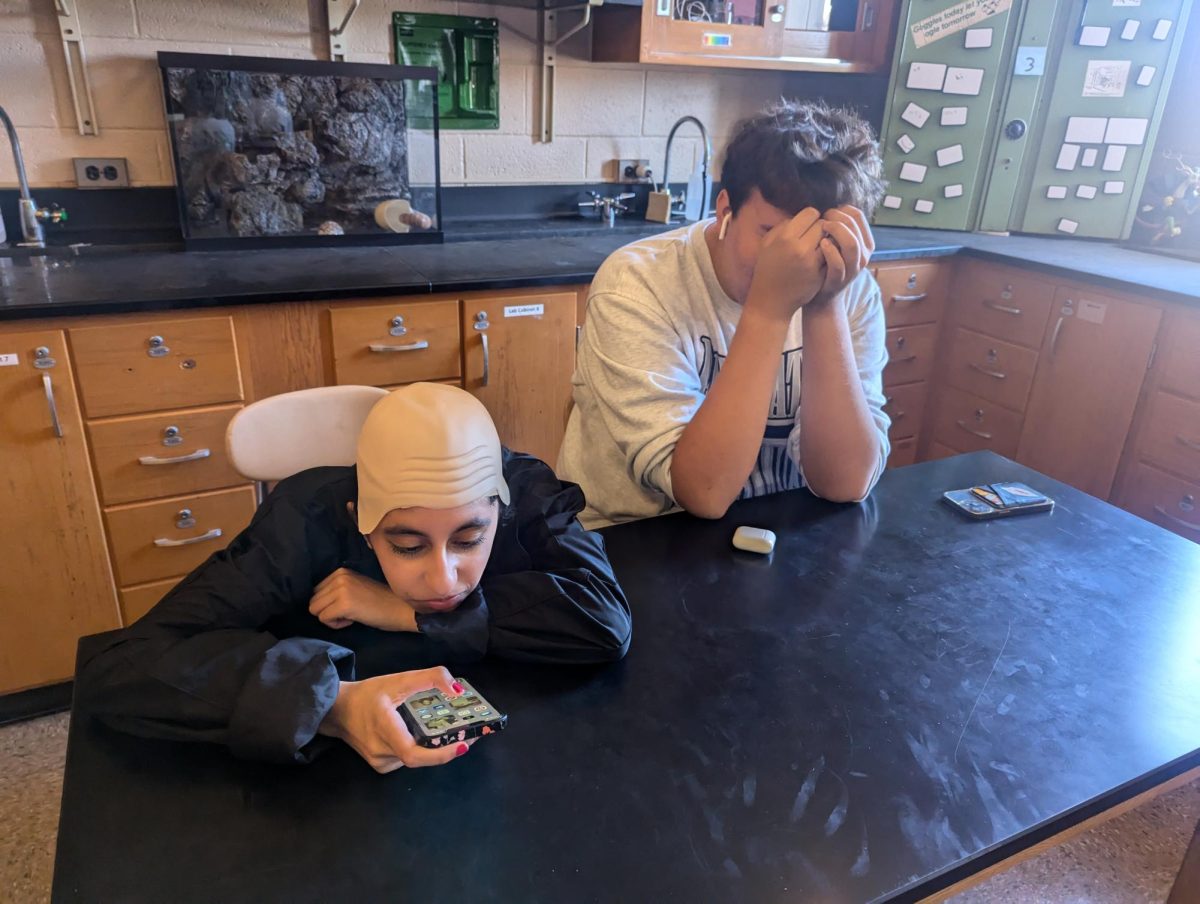

It’s an early Monday morning and you’re sitting in first period, when your teacher turns to the class and asks a simple question about the lesson. The girl next to you has her eyes closed and her head down on the desk. The boy across from you has AirPods in his ears while scrolling through his TikTok feed. You consider answering the teacher’s question, but amidst the awkward silence hanging in the air and the sleep not yet rubbed out of your eyes, you hold back.

Across the building, students sit silently in classrooms of lecturing teachers, who ache for a single hand to be raised, a voice to be heard, every day. Student participation is at a standstill, and it takes a toll on the teachers in front of them.

“It’s a challenge. You sometimes think, ‘what am I doing wrong? Is there a disconnect between me and them? Am I not engaging them enough that they’re bored and that they’re on that phone?” Mr. Eric Lorandeau, a North Penn High School History teacher, commented.

For teachers, students’ disengagement in class feels like its own disapproval of their lesson. It provokes frustration and discouragement among staff members when students blatantly ignore or stare blankly in the face of a class-wide question, especially when trying to implement different engagement tactics.

“It’s challenging for a teacher, too. It’s not fun for us either. It can get a little frustrating because sometimes the tricks don’t work,” Lorandeau.

Low engagement across the board sparks questions about the cause behind it. One common reason is that students’ social concern of perception by their peers dwindles participation down lower, studies have found.

“[Students] were found to have fear of participating since they did not want to be wrong in front of their peers. Students talked about worrying that they would look dumb if they answered incorrectly, or made a comment that was not viewed as intelligent.” explained a study published in the National Library of Medicine.

“It’s that social fear of getting the wrong answer and everyone looking at you and judging you. For a teenager, that’s a pretty high concern,” Lorandeau further explained.

Additionally, cell phone use has been credited as another part of the issue. They pose as a distraction within classrooms, and students have a hard time keeping their focus on the person in front of them as opposed to the screen in their hand.

“I joke that it’s like we’re teaching a bunch of addicts. [Cell phones are] just like a part of us; they’re like an ascension of us. I think we live in an age where cellphones are comfort. You can kind of hide behind that,” Lorandeau said.

However, North Penn High School’s recent implementation of a no cell phone rule has decreased the severity of this issue. Many students shared that they felt less drawn to their phones when it was kept away in their school bags, rather than sitting as a temptation on their desk.

The COVID-19 pandemic is another factor that seemingly decreased the rate of in-class student participation exponentially. Teachers have observed that when students came back in person, they were significantly less engaged in the classroom.

“Those middle school years are very formative in terms of negotiating personalities and interacting with people, and interacting with people that you don’t necessarily like. Because of the pandemic, all of that stuff was just taken away, so then you come back into a normal classroom, and those skills that were ever developed,” explained Lorandeau.

The issue of low participation is an important one to recognize; not only is it hard on teachers, but it prevents students from gaining the important benefits to be gained from participating. As a student, engaging in class reinforces important social skills and information retention.

“One of the skills that a lot of students don’t get, is you’ll have to be in places you don’t want to be in. It’s okay to be bored and disconnect. We need to train you, the world doesn’t operate in 30-second sound bytes. It’s good practice for life. Those skills you develop, they’re with you for the rest of your life. So, why not develop them now, in high school?”

Furthermore, raising your hand can also raise your enjoyment within that class.

“You’re gonna make class more enjoyable for you. Those forty minutes are going to go by quickly if you’re talking and you’re engaging. Students don’t think about it that way, that this makes class more enjoyable for themselves,” Lorandeau said.

Lorandeau offers options such as emailing him after class about your lesson takeaways for a participation grade as opposed to raising your hand for those who feel less comfortable sharing out in class. During lessons, he shared, he will also use tools such as “word clouds” that share anonymous answers and turning and talking to a neighboring peer to discuss questions, rather than doing so in front of the whole class.

“A traditional participation grade really benefits the extroverted among us, and it can hurt the introverted. I never put it in that kind of view before, and then once thought of it that way I was like, ‘I don’t like that.’ So, I wanted to get options for students,” Lorandeau said.

Teachers offering options different from the traditional methods may help encourage participation. Still, class engagement relies largely on a student’s willingness to contribute. No matter how you do it, participation in class is important for you and your teachers. So, the next time you debate about putting your hand up, raise it high.