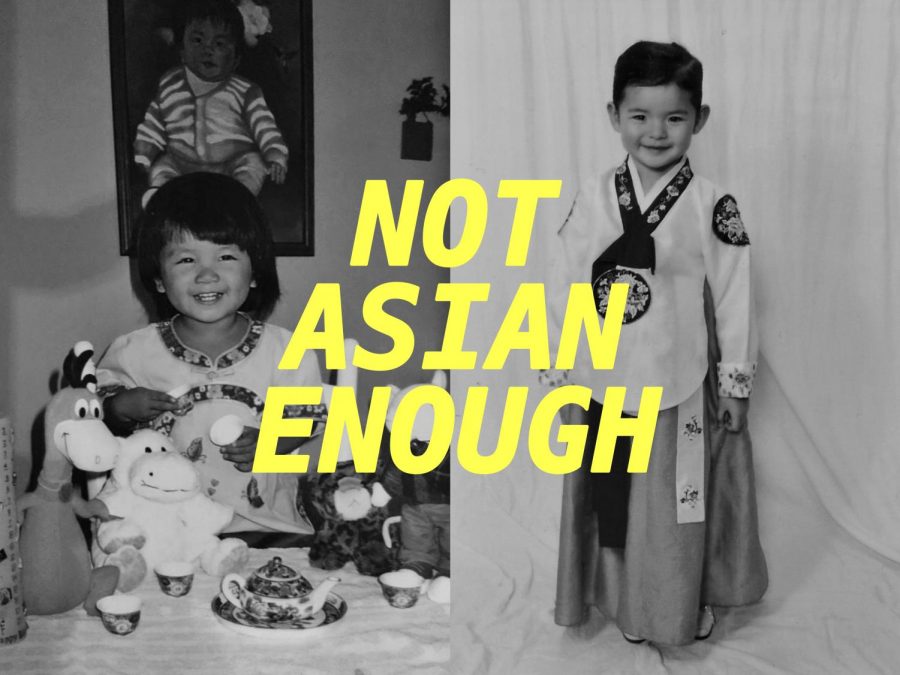

Stuck between two worlds: the struggle of not being “Asian enough”

The following article is a part of a series I created in honor of Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

2 years ago, I went to visit Vietnam and Cambodia, the countries my parents were born in, for the first time.

It was also the first time I strongly felt isolated from who I would consider my own people.

I didn’t know how to speak either language. I struggled to fit in with the cultures. I felt more like a tourist rather than a member of the community.

I didn’t feel like I belonged there.

That feeling was always present in the back of my head all throughout my life, but this time, it was my reality. Over time, however, the idea faded and I forgot that it ever came into my mind.

For some biracial or adopted people, this is what it feels like every single day, and it’s something they can’t ever forget about. Each and every single day, they have to fight against the concept of not being “Asian enough.”

DANIELLE STABER

NOT ENOUGH OF EITHER ONE

North Penn High School junior Danielle Staber grew up living the best of both worlds being half Korean and half white. For a while, both cultures were present in one household.

But things changed after her parents divorced and her mom remarried to another white man. Staber would be with her dad throughout the week and see her mom during the weekends. Although her dad attempted to keep her and her sister connected to their Korean heritage, the only time she would ever get to practice her Asian culture, other than basic values, is during celebrations with her extended Korean family. Because her mom is also more Americanized, since she arrived in America at a young age and married two white men, the Korean culture isn’t as drilled into their day-to-day lives as much.

From a young age, Staber found it difficult to fit into both lives: her white side of the family and her Asian side of the family.

“It was a lot of cultural shock on both sides. My white family didn’t understand my Asian values or cultural traditions and my Asian family didn’t understand why I wasn’t more like them or why I was more ‘whitewashed’. There had been events where my white family didn’t really understand what would be a racist comment or not a politically correct comment. My aunt once referred to someone as oriental which isn’t exactly a politically correct term anymore. She never even thought about it when I was sitting with her and it was just jarring because I feel like most people would censor themselves if they were speaking in front of someone of that race, but they just didn’t have any idea because they didn’t really think anything of it,” Staber explained.

“Although I really enjoy educating the other side of my family on what these traditions and cultures mean to my Korean half and Korean heritage, sometimes it’s difficult when they’re almost refusing to understand that side. I have a stepfather and his family is southern white and that side of my family is way less racially aware than my dad’s side of the family. When I’m with them, I don’t really bother trying to explain any of the stuff because I know it’s something they don’t necessarily care about. But when I’m with my dad’s side of the family, who I’m closer with, it’s a little bit easier for them to understand, but it’s not the same,” Staber said.

Staber never felt like she belonged to either side of herself growing up, but most of the time, she identified herself as white because she never practiced her Korean culture that often.

“I never really felt accepted by either culture. When I was with my Korean family, it was hard to understand that side of myself because there was a language barrier and I couldn’t be as close with that side of my family when I couldn’t get past certain things. I never felt like I could fully be a part of my white family because of their obliviousness to the fact that I’m different from them. It was difficult for me to make Asian friends when I was little because there was always a divide with language. They knew how to speak their family’s language and most of the kids that were friends with each other who were Korean usually were the kids that could speak it versus the kids that couldn’t. I was one of the kids that couldn’t. I couldn’t relate to them in the same way the other fully Korean children could. It was also that my white friends couldn’t understand the person that I was and that I’m not just one thing and I’m not just the other thing. It was always that I was different from them or that I didn’t look like them. It made figuring out my identity harder when I was younger,” Staber said

CONNECTING TO HER KOREAN SIDE

Because Staber isn’t fluent in Korean, she misses out on the level of connection language can bring.

“A lot of my cousins speak multiple languages like English, Spanish, Korean, and Hebrew and they know sign language. I only know English. My mom really wanted to put me in Korean school, but never did. To me, it’s important to know the language because I wish that there was less of a language barrier between me and my grandmother. It’s important that I connect to that side of me because I feel like on some level, that’s one part of you that you can’t understand until you know the language,” Staber said.

Whenever she hangs out with her Asian friends, it feels like she’s going to one of her relatives’ house because they’re more in touch with that side of themselves.

“It feels familiar, but it feels like I’m stepping into unknown territory. Going into someone’s house who is Korean, I understand the values that they have and the habits like taking off your shoes before you go into the house or having a rice cooker with rice constantly in it. It feels familiar, but I also feel like I don’t know as much as I should. It’s hard when their family expects me to understand the language or be a certain way that I’m not, and it almost feels like they’re shaming me because I’m not as Korean as they think I should be,” Staber explained.

NOT LOOKING LIKE THE REST

Compared to her sister, Staber looks more Asian and when she’s with her white side of the family, she tends to stand out more.

“When I went to Austria for a family reunion on my dad’s side, which is my white family, everyone there was white and I was the only person, besides my sister, that was biracial. It was clear that I didn’t look like them and I got a lot of stares and comments from people,” Staber said.

Oftentimes, when she was younger, Staber used to wish that she was just white.

“I was the kid that faced a lot of insecurity and a lot of social anxiety and it didn’t help that I didn’t look like everyone else. It would always make me feel like I was different no matter what I did and I never wanted to be different. I just wanted to fit in and be normal. But back then, my definition of normal was so skewed because I was little and didn’t know much about the world,” Staber recalled.

“A lot of it came from my insecurities with my outer appearance because I wanted to be like everyone else. I thought being normal was being like the majority, which was white,” Staber said.

CONNECTING BOTH LIVES

During Korean New Year, her white step-siblings join Staber and her blood sister Claudia to celebrate at their grandmother’s house.

“That’s the day where my white family can kind of immerse themselves and relate more and be a part of that culture because they’re involved in the bowing ceremony and the receiving of the new year’s advice. That’s the only day where they can be a part of that side of myself. It’s an experience that we can share together,” Staber said.

Being both Asian and white, Staber feels like it has brought both sides of her family together.

“When there’s an opportunity for my family to come together and do something, I feel like that’s what brings us closer together through my biracial identity,” Staber said.

ADDRESSING THEIR DIFFERENCES

Despite not being completely immersed in her Korean side, Staber still wants to keep it alive by passing down traditions to her future kids and continuing to prioritize Asian values daily.

“To the people that just say, ‘you’re not Asian enough,’ I say, ‘maybe I’m not as Asian as you or maybe I’m not as connected to Korean culture as much as you are, but I carry that part of myself with me every single day.’ I just don’t like it when people just assume that because I’m half white and don’t practice it as much as they do, I could just turn [her Korean side] off,” Staber said.

Like any other Asian, Staber also faces racism and it’s no different than what a full Asian person would go through.

“Some people don’t understand that I still face racist judgment because I’m Asian. They just assume that I get white privilege because I’m half white, but I look more Asian, so I don’t. [Her Korean culture] will always be there,” Staber said.

Being Korean is something she will never not be proud of.

“Even if people say I’m not Korean enough because I’m half white, it doesn’t matter what they say because I’m proud of that half of myself,” Staber said.

ACCEPTING WHO SHE IS

For as long as she could remember, Staber thought being just one thing was normal. Now, she appreciates the fact that she can be both.

“I’m grateful that I don’t look like everyone else because it makes me special,” Staber said.

“The best part of being both is that I have a less narrow view of the world than a lot of people do. It’s expanded the way that I see the world and the way that I interact with other people and the way that I feel empathy and the experiences that I try to understand from other people. It’s opened my eyes to how ugly the world is, but it’s also opened my eyes to how beautiful the world is because of how much diversity there is. You can understand so much more about the world than you could if we all were the same,” Staber said.

KATE STECHERT

FOUND AT LAST

At a month old, North Penn High School junior Kate Stechert was found and put into an orphanage after she was abandoned and left out in the streets of China.

When she was 10 months old, she was adopted through an agency where families traveled to China to adopt girls around her age. From that orphanage, Stechert had around 15 other people she could stay in touch with to this day. Most of the families lived in the same region, so Stechert grew up with a lot of the girls from the same orphanage.

“We see each other every year. That’s always helped keep me connected with them. We call each other sisters because we’re all we really have,” Stechert said.

“It’s comforting to know that there’s people with the same story as me and they’re all really close to me,” Stechert said.

Stechert and her family have no information on whether or not she may have other siblings. The closest possible sibling she has is another girl who was found with her when they were a month old. The orphanage put them in the same crib, assuming that they were siblings, specifically twins, and throughout most of their lives, that’s what they believed. As they got older, they noticed that they had many physical differences; the other girl has cerebral palsy which is rare for only one of the twins to have.

KEEPING HER CULTURE ALIVE

Growing up, her mom was very open to diversity and celebrating other cultures, so Stechert always knew she was racially different from her mom who was white. Her mom sent her to Chinese school for 4 years where she learned Chinese and how to do traditional dances.

“She wanted me to know where I came from because my family’s not that big on my mom’s side, so she wanted me to have a good life and to experience my own culture because she couldn’t provide [the cultural experience] herself,” Stechert said.

As a child, Stechert was surrounded by other Asian kids who made her feel welcomed. She never had a problem immersing herself in the Asian culture growing up because she made a lot of close Asian friends who introduced her to the food and traditions.

“I would go to [her friend Stacy’s] house all the time and all of my other Asian friends’ house. They would be speaking different languages, eating different food, and practicing different customs. I never felt like I wasn’t welcomed. It was just weird thinking that I was the same as my friends, but I don’t go home to the same thing,” Stechert said.

UNEXPECTED NEWS

A few years ago, Stechert took a DNA test and found that she wasn’t Chinese, despite being adopted from China. It turned out that she was actually Indonesian, Papua New Guinean, and Japanese.

“It kind of changed my mindset of who I am. I always gave a general statement that I was Asian, specifically Chinese. Knowing the reality of it and how different I am from the people I’ve been around with my whole life is interesting,” Stechert said.

Due to the lack of Indonesian, Papua New Guinean, and Japanese people in the area, Stechert has found it difficult to connect back to her roots.

Since she was adopted at such a young age, Stechert never grew a strong connection with her blood-related family, so it’s not as big of a priority to find out who they are. If she were to get the chance to see them, she would take it, but she knows that her true family is the one she currently has now.

“I always think about how my life would be like if my parents didn’t put me up for adoption or just leave me. I always have wondered what it’s like to know your parents and know that you look like them. Being raised this way, I can’t look at my parents and think that’s what I look like,” Stechert said.

THE PRESSURE TO BE MORE ASIAN

Knowing that she was still Asian, despite being adopted, Stechert always felt the pressure to be more Asian.

“For me, it’s kind of annoying how so many people around me would bring up all of these (cultural) holidays, but I don’t celebrate it at home. I kind of wish I knew more about it or had the same experiences as them. I get to go to all of these celebrations with my friends, but I go back to my white family and there’s a different culture. I just don’t feel like I fit in,” Stechert said.

One of the biggest differences between Stechert and her friends, besides her being adopted, is the fact that most of them can speak their ethnicity’s language. Sometimes, it makes her feel a little isolated from everyone else because she doesn’t understand them.

DEALING WITH RACISM

Stechert often feels like she can’t discuss racism because she’s afraid of people silencing her experience due to her upbringing. People expect her to have white privilege because her parents are white.

“I don’t experience [white privilege.] I still put that I’m Asian on every application because I can’t change that no matter who I grew up with. I do experience racism, but I feel like I can’t speak up about it because I wouldn’t be taken seriously,” Stechert said.

CULTURE APPRECIATION

Despite not growing up as your typical Asian, Stechert is still proud of who she is and where she came from.

“It has really impacted me by opening my eyes to how much there is out there that I don’t know or how much is left untouched and I will never know. It’s because of what I’ve been through and how much I’ve experienced in two different worlds that I could see all of that,” Stechert said.

Christiana N. • May 18, 2020 at 2:01 pm

Really cool article. I think it’s awesome you brought to light a very important discussion and topic that a lot of people don’t really think about (myself included). It was great to learn about different points of view, and these girls’ experiences. Will definitely have a more open mind with racism and the topic of the differences with race and adoption (which is a topic I don’t normally think about). Great job to the two girls and to Hannah for opening the discussion. (And Happy Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month)