Survey says over 90% of NPHS students cheat – Is it the best means to the end?

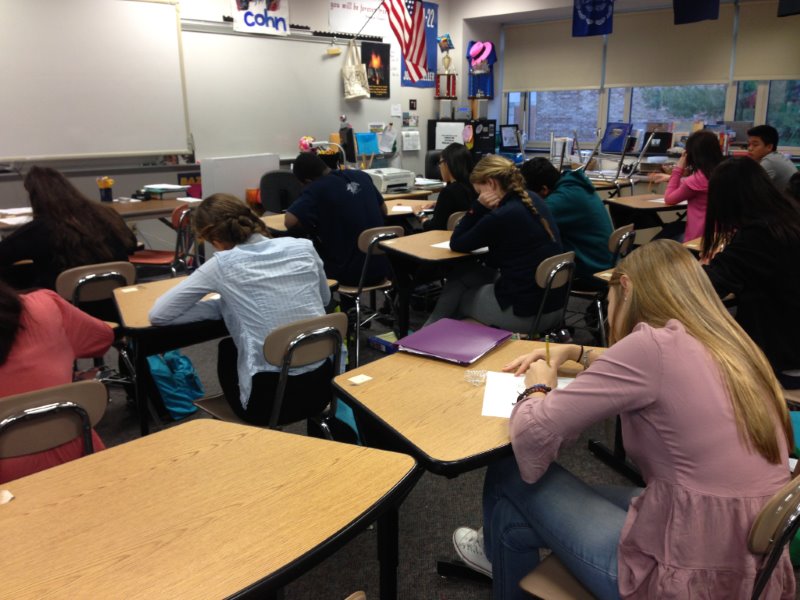

North Penn High School students take a quiz in English class. A recent survey of students at NPHS revealed that cheating in one form or another is widespread, but not unique to high schools across the country.

November 24, 2014

Identities of students interviewed for this article have been protected.

The conversations are ubiquitous in classrooms, hallways, the cafeteria, and just about anywhere else students think teachers won’t hear them.

“Hey, did you do the math homework? Can I see it?”

“What was on the history test? I’m taking it next period.”

“I didn’t know the answer to a question on the test, so I looked at what the kid next to me had on his paper.”

Listening to these comments, it’s easy for one to feel as if academic cheating has become accepted as part of everyday school life among teenagers, an easy way of achieving in a culture that defines teenage success on grades and college acceptance letters.

In a recent survey given to North Penn High School students, over 90% of respondents admitted to cheating on some form of schoolwork at least once. The survey, given to 220 North Penn students taking classes at 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and AP levels, asked respondents to report whether or not they had ever copied homework or looked off of another student’s paper during a test.

The results revealed that 92% of students, regardless of what level classes they took, admitted that they had copied another student’s homework.

More students, 95% of those surveyed, said that they had let other classmates copy their homework. Among respondents who took AP classes, over 98% claimed that they had given their homework answers to a friend.

In addition to cheating on homework, about 51% of respondents confessed that they had looked off of another student’s paper during a test, with the results showing little variation among students who take AP classes and students who do not.

Only two of the 220 survey respondents claimed to have never cheated at all.

Such cheating is certainly not exclusive to North Penn; a 2010 poll by the Josephson Institute Center for Youth Ethics revealed that 59% of high school students across the country had cheated on a test in the past year.

Though cheating is prevalent, only a small amount of respondents at North Penn reported getting caught while cheating in any form, whether on homework or on a test; a mere 15% of students had been called out by teachers for cheating, with even fewer receiving punishment for their actions.

In a room filled with 30 kids taking a test, it’s easy for students to quickly glance at a classmate’s answers and difficult for teachers to catch students doing so. But part of the reason why cheating is so hard to catch is because it isn’t limited to just the classroom. In an age where almost everything a student needs to know is just a quick Google search away, looking off of somebody else’s test is only one of many ways to cheat.

“People [cheat] in many different ways,” said “Kelly,” a junior at North Penn. “You could just look off of the paper of the smart kid next to you, or write vocab words on your hand, or store equations on your calculator. People get the answer key before they take the test, look up homework answers online, or copy the homework from other people.”

“Kelly” went on to say that “[people who cheat] are people who care about their grades. Everybody cheats.”

The decision between spending hours reading a textbook on your own and minutes reading notes online is an easy one for many teenagers. And these online resources aren’t hard to find; there are websites devoted entirely to notes for specific courses and textbooks, especially at the AP level. The answers to many worksheets not created by the teacher assigning them can be found, often verbatim, on Yahoo answers or Quizlet. Simply put, part of the reason that students cheat so much is because there are so many ways to cheat.

But convenience is only one of the many factors that students consider when they decide to cheat on homework. Balancing busy schedules of extracurricular activities, family obligations, and after-school jobs causes many students to be strapped for time, making these quick solutions seem like the only solution.

A North Penn junior who participated in the survey and wishes to remain anonymous said that students “cheat [on homework] when they have no time.” The student also justified copying homework, explaining that the purpose of homework is to ensure that students understand the material being taught in class. Therefore, the student reasoned, “if you know what you’re doing [in class], it’s not really cheating.”

Ellen McKee, an 11th grade AP English teacher at North Penn, commented that “[students] are all panicked, and there is such a culture of cheating that they don’t mind [copying homework]. Some kids have the mindset of ‘I just need to get through this class.’ We’ve become so grade-conscious that we’ve lost the meaning of learning.”

McKee went on to say that, while cheating might seem worthwhile to students in the short-term, “you always pay when you take a shortcut. If you cheat your way through [school], there’s no growth. And who wants to be ignorant?”

And it’s not just teachers who think that the focus of school has shifted away from learning and growing as a person; “Kelly” claimed that “school has become less about getting a good education and more about getting good grades to get through. Now, it’s about the easiest way to pass instead of learning.”

To students, the pressure to succeed comes from almost everywhere in their lives. “Sarah,” a junior at North Penn, declared that “there’s so much pressure from school and home that students feel obligated to cheat [in order to] get good grades.”

However, Marjorie Diegue, a guidance counselor at North Penn, sees the stress coming not from parents and teachers, but from the students themselves.

“Students perceive pressure from their parents,” she said, explaining that most of student’s stress occurs when they measure themselves against other students, particularly those who have been admitted into exclusive, Ivy League colleges.

“Students feel overwhelmed,” Diegue said, “and to them, it’s easier just to grab [answers] from a friend.”

Diegue also noted that there seemed to be no correlation between a student’s success and cheating. “I see kids who fail who cheat, I see kids who pass who cheat,” she said.

For many students, the blatant dishonesty of cheating is easily justified when they consider what’s at risk. Constantly bombarded with reminders that “colleges look at grades” and “good grades get scholarships,” they subscribe to the Machiavellian concept of the ends justifying the means. Cheating seems acceptable if the alternative is not getting into the college of your choice or taking on thousands of dollars in student debt.

However, in the rare cases where cheating is detected, the short-term consequences are severe.

In recent years, cheating scandals among both teachers and students have shaken various school districts across the country. This past spring, four teachers and the principal at an elementary school in the Philadelphia School District faced criminal charges after they allegedly changed students’ answers on standardized tests. And in 2012, more than 80 students at Stuyvesant High School in New York were caught using their cell phones to share answers during state exams. The consequences faced by the people involved in these scandals were severe, but still many students across the country complete assignments and tests dishonestly.

At North Penn, every student is required to sign a form at the beginning of each school year recognizing the severity of and the punishments involved with plagiarism. According to the North Penn High School Parent and Student Handbook, plagiarism is “the act of using another person’s ideas or expressions in your writing without acknowledging the source.” Cheating, mentioned in the same section of the Handbook as plagiarism, is defined as “copying homework or test/quiz answers from another student, or enabling someone else to do so.”

Also listed in the Handbook are the consequences involved with cheating and plagiarism: a zero on the assignment for the first offense, a zero and a possible suspension for the second offense, and a zero and a three day in-school suspension for all subsequent offenses. While the use of anti-plagiarism sites such as turnitin.com by teachers helps to cut down on dishonesty in essays, minor, everyday cheating offenses cannot be constantly monitored. Copied homework is almost impossible to distinguish from homework that took hours to complete honestly. Given this, some students feel as if there is no reason not to cheat.

This relaxed attitude towards dishonesty follows students past graduation, affecting them as they continue on with their lives outside of a school setting. A 2012 survey conducted by The Society of Human Resource Managers found that 53% of resumes contained false or misleading information. Is this real-world dishonesty coming from the continuing habits of people who cheated their way through school? Or do students feel as if it’s okay to cheat in school when they can continue to cheat once they graduate?

Kids in high school do not always consider the long–term impacts of their actions if the short-term result is success. To many stressed and overwhelmed students, cheating is nothing more than another acceptable way of getting that coveted college acceptance letter, no matter what the lifelong impact may be. However, a college acceptance letter is not the end of the line – in truth, it’s only the beginning, which should raise questions in students’ minds about what cheating is really setting them up for.

Knight • Dec 5, 2014 at 10:51 pm

Cheating is wrong. There Is one factor that seem to be a problem, one is that the student is improperly leveled. You should not take AP Bio course just because it is an AP course and get answers from students last years notes. and cozy up to the smart kids who to get a worthless five without taking the course. That’s called fraud and it sickness me how the AP students are the biggest offenders from stories this year. It’s so easy to say no, and not to respond to the text message for answers or to have the cute girl in AP bio to suck up to you for notes. Say no and tell her/him off!!

Anonymous • Nov 29, 2014 at 9:55 pm

Brianna • Nov 26, 2014 at 8:33 am

This article needed to be written. The name “North Penn” could easily be replaced by any high school and frankly I see it go on in the majority of my college classes as well (especially my upper level science courses). Habits of poor academic practices will follow students into college and more than likely plague them in the real world. This article is very relevant and well-written.

Curt Reichwein • Nov 26, 2014 at 8:07 am

In the end the ones that truly lose are those that cheat.

kimbo slice • Nov 25, 2014 at 7:15 pm

I disagree with this and i dont like it at all. If you are going to slander the students like this then point the finger at yourselves before anything