OPINION: The problem with Black History Month

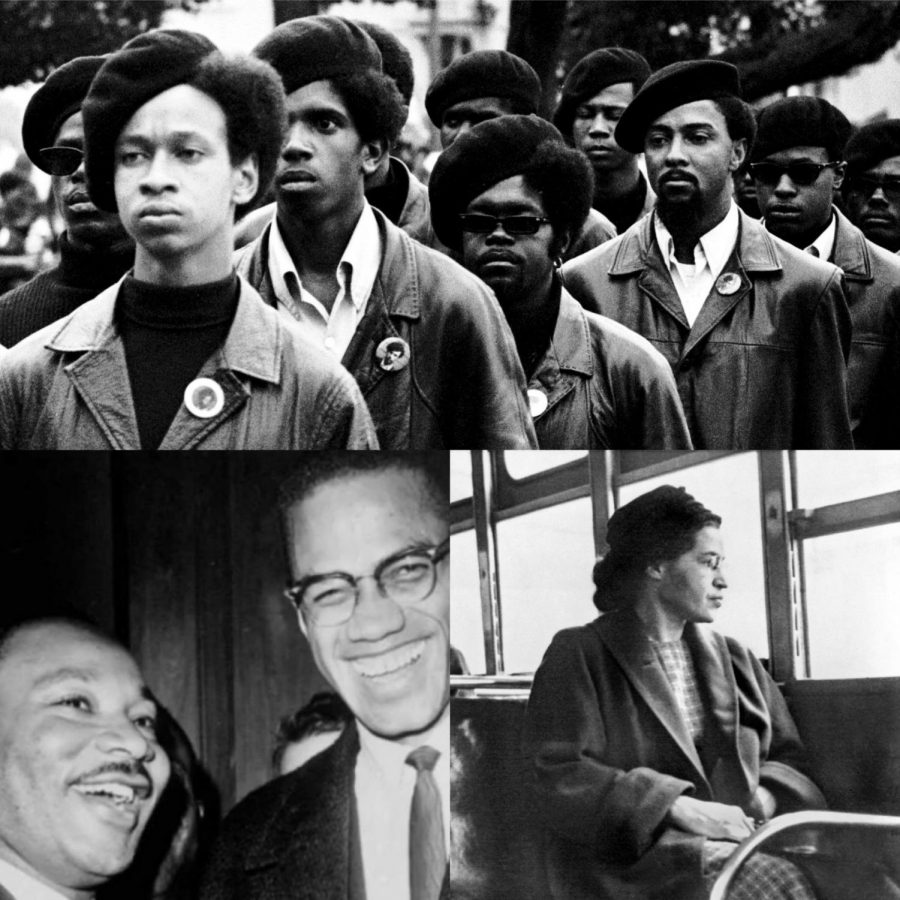

Top: Black Panther Party. Bottom (L-R): Martin Luther King, Jr.; Malcolm X; Rosa Parks

While we’re in the midst of February, we celebrate the African-American heroes who paved the way for our freedom and pursuit of happiness. We are eternally in debt to those who shed blood and died just so that we, their successors, could live better lives. As much as people shine light on the few leaders who made a difference for African-American culture, there are many more figures who aren’t given the spotlight. Quite frankly, this is my exact issue with Black History Month and why I personally believe that we as a society should make a motion to dive deeper into our history year-round, effectively removing Black History Month entirely.

Before there was Black History Month, a recognition called “Negro History Week” was enacted in 1926 by historian Carter G. Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History to be the second week of February due to the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln (February 12) and Fredrick Douglass (February 14). The black community celebrated these two birthdays ever since the late 19th century, so this seemed necessary for the time period. 44 years later, the first Black History Month was celebrated at Kent State University in 1970; U.S. President Gerald Ford acknowledged this by encouraging the American people to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

There are three glaring issues with the “celebration” of Black History Month ever since its first demonstration: we were given the shortest month of the year, we don’t dive deep enough, and new forms of black history are met with too much animosity.

I understand that it seemed like the transition to Black History Month from what it was before made sense at the time, but either way, 28 days is still too short to be celebrating a whole race’s advancement throughout our nation’s history. Even then, the brevity of the holiday is not where the problems lie.

It seems like every time I see a promotional poster for Black History Month, I see the same few faces: the likenesses of Martin Luther King Jr., Fredrick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman. Don’t get me wrong, two of the most influential runaway slaves as well as a revolutionary social activist deserve all the praise they get. But what about Malcolm X, the Black Panthers, Maya Angelou, Jesse Owens, Marcus Garvey, or other black leaders that have suffered and paved the way and don’t get the spotlights they deserve? It’s disappointing to see because these people were just as significant as the superstars we glorify.

Currently, we still tend to brutally criticize instances when black people push the envelope and create controversy. Ever since August 2016, the NFL national anthem protests initiated by former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick were met with backlash from the media, citing that kneeling was “un-American” and “disrespectful to veterans.” The protest was to shed light on the systemic issue of police brutality against African-Americans in the United States, which has nothing to do with the armed forces. What about the numerous veterans who came out in support of Kaepernick’s protest? Are they un-American too? In response to Beyoncé Knowles-Carter’s Black Panther Super Bowl performance, conservative political commentator Tomi Lahren claimed that the party was a terrorist organization and said that if Knowles wanted to properly fight for civil rights, then she should start at home since her “husband [Jay-Z] was a drug dealer.” Fox News host Laura Ingraham told NBA superstar LeBron James, a member of the Cleveland Cavaliers at the time, to “shut up and dribble” in response to James’ criticism of President Trump. I can go on and on about current black celebrities being demonized for continuing the need for racial justice. If we sustain this antagonization, the progress that our predecessors laid for us will go to waste.

The initiation of Black History Month was great for its time: a time when any accomplishments made by African-Americans were barely mentioned. Though we live in a different world now, the ignorance that prevented racial awareness from moving any further still seems to be prominent. While this month is considered a celebration, it is also a mindset that needs to be present in all of us so that we may socially advance in our country. The whole purpose of “Negro History Week,” which evolved into Black History Month, was for the hope that one day we wouldn’t need it anymore: a day in which black history will be acknowledged for 365 days and not just 28. Black history is American history.

Brent Thacker • Jun 14, 2020 at 9:30 pm

What about Asian American, Indian American, Mexican American, on and on, why can’t we just be American?

Brent Thacker • Jun 14, 2020 at 9:26 pm

I get it, also, when can we burn the one dollar bill, after all, the supposedly father of our country was a slave owner.

John Utsey • Mar 3, 2020 at 2:51 pm

Very powerful article. You’re absolutely correct Black history is more than a month. Keep up the great writing.

Rebecca Glick-Luby • Mar 2, 2020 at 8:47 am

Black history is American history! Excellent article, thanks for writing it.

Brian Haley • Feb 28, 2020 at 3:44 pm

Interesting read. Thank you for sharing Simeon